Pedro Barateiro

Sequel

Basement Roma

June 28 — August 30, 2017

Mythologies are dead, they have always been. But even as corpses, they’ve been used as political strategies to manipulate fiction and facts. Fictional narratives have defined culture, its historicity, its legacy. Drama. Goosebumps visible in our skin. Chills. The amplification of the voice. The soundtrack of the film. Attitudes change. Behavioral patterns change, adapting to new forms of recognition. The stream of our social media accounts translated by ignorant algorithms. Liquid and opaque forms of identity. The movements of the body. The most superficial of all gestures can never be taken lightly, even if it tries hard to be disguised with bright colors, with feathers and fumes.

A year ago, exactly on the same date of the opening of this exhibition at Basement Roma, I arrived in Los Angeles. I had never been to the city, and to me L.A. represented the geographical point of the production of what is called the spectacle, a sort of dead-end or end point of Western civilization. The amount of fiction written for films, tv and all sorts of shows that come from there, generates an overproduction of narratives that intend to alienate the spectator while mixing and re-creating personal and historical moments. The entertainment business is a form of capitalist production that alters our perspective on the events happening around us. For example, the way politics is represented in fiction is, in many cases, deprived of ethics. And it continues to do so through an ever growing network of mythologies.

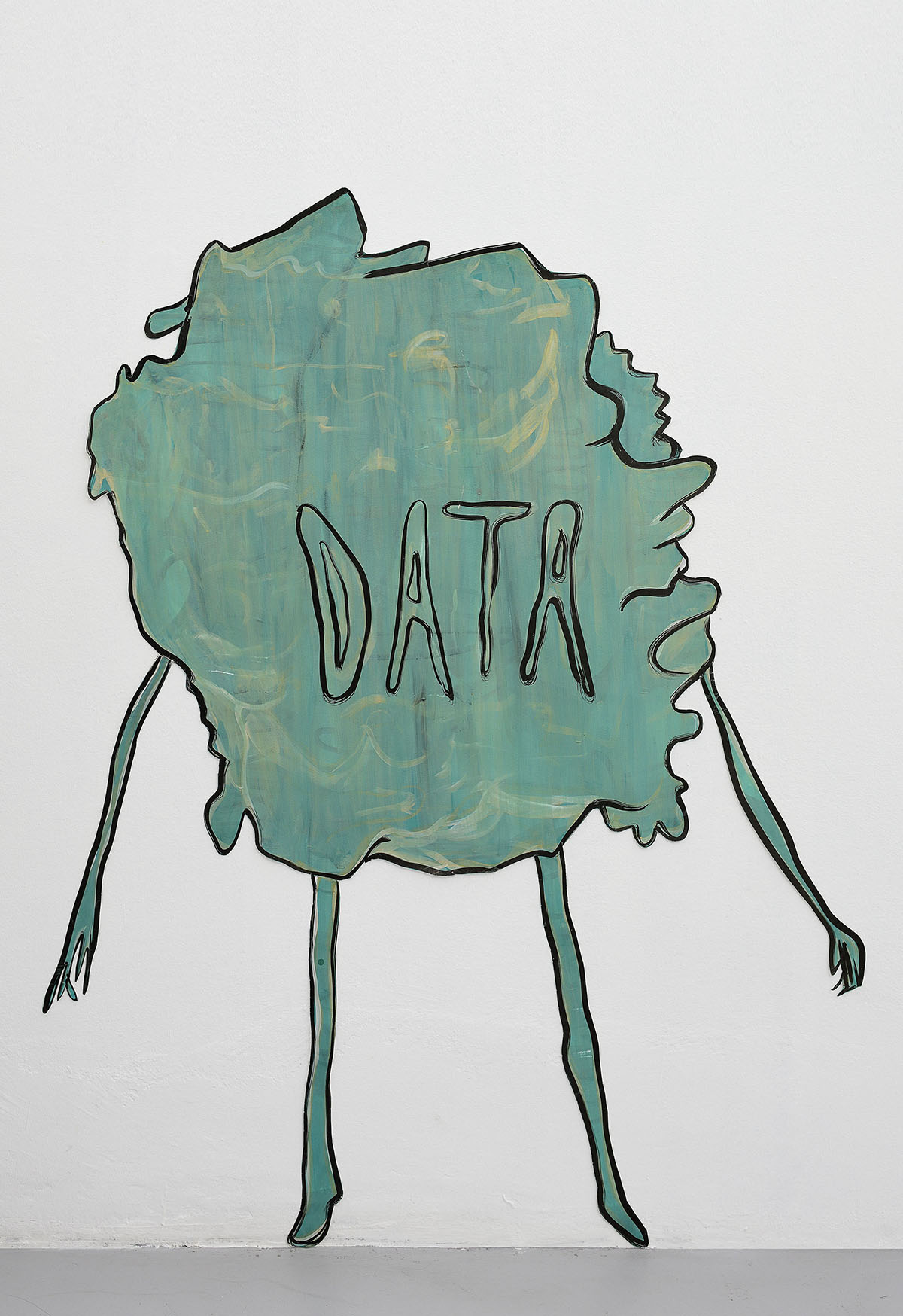

If we think carefully on the process of how narratives and mythologies travelled from Ancient Greece, re-interpreted through Rome, we can analyze the process of how culture in the West has been produced, how philosophy, fiction writing, poetry, music and the visual arts, have transformed themselves as part of a capitalist machine. The mass production of images, the representation of the human body, the representation of nature on Western culture changed quite drastically since early capitalism. Under forms of appropriation and colonization, our interactions within the available communication systems are surveilled and monitored. Our exchanges are now translated into big data. And data has now surpassed oil as the most valuable resource in the world, and we are all contributing with different types of content. The goal of fiction today is to pretend that there is a continuation, that the grand narrative never dies. Season after season of endless stories that colonize our lives. Our brains have been programmed to accept Trump as president via Frank Underwood in House of Cards. Our imagination was colonized so we could accept that type of person as a political figure.

The title I gave this exhibition, Sequel, refers to the disbelief of Western traditions of narrative and representation in the moment we’re living. But I need to ask myself and you: how can our imagination resist? How can we stop our imagination from being colonized by these myths? What can art and thought do facing these forms of fictional politics? What is left for us to write? Are we supposed to resist this endless present of small narratives that hide the big narratives of capital? Should we think about an ecology of production of data, an ecology of immaterial labour?

In her book, The Responsibility of Fiction Writing in Neoliberal Capitalist Societies (Duvida Press, 2014), writer Leonora Jones talks about the necessity of awareness in the growing use of text in our communications, specially in the interactions in social media, and how data is used, transformed and profited by capital, as it manifests the exposure and altered states of subjectivity produced within a neoliberal post-capitalist society. Along with the growing abstraction of value and human interactions, new forms of passivity, of spectatorship and consumption require a response to new models of action and community. The apparent fluidity of circulation and distribution are represented by a materiality that is not fixed. Jones asks: “How can we represent a state of constant transformation, if it changes shape at any moment, like an ecosystem needs to adapt and mutate to the surrounding environment?” And she continues: “We should act in a form of conscious resistance, not as passive spectators”. Jones mentions Naomi Klein’s NO LOGO (Picador, 1999) and her take on Milton Friedman, who Klein claims to be “the architect of the global corporate takeover”. Jones underlines her idea with the fact that Klein illustrates this chapter of her text with footage of two members of the activist group Biotic Baking Brigade, who threw a pie at Milton Friedman, when the economist was leaving a corporate conference in San Francisco in 1998.

Curated by João Mourão & Luís Silva

All Images:

Courtesy the artist

Photos by Roberto Apa

Supported by

República Portuguesa

Cultura Direcção-Geral das Artes (DGArtes)